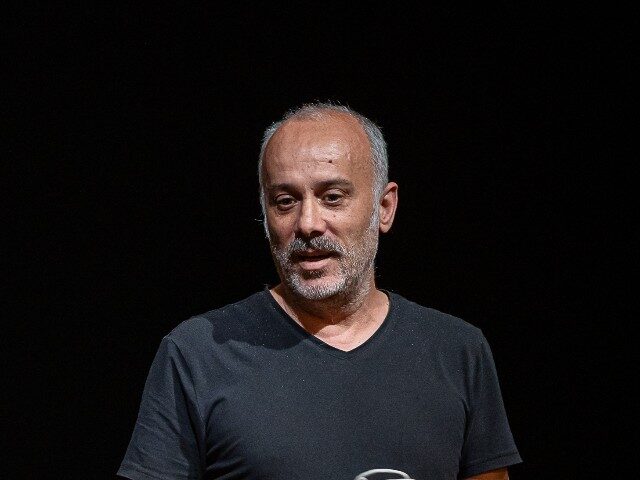

“The selfish giant” stages the story of a giant so in love with his garden that he forbids entry to anyone, especially to children. Thanks to a wall, the giant succeeds in his intent; nevertheless, the garden soon becomes sad, cold and covered with snow. Just the children’s return could make the garden bloom again. The show is based on the fairy tale of the same name written by Oscar Wilde in 1888 for his children, part of the “The Happy Prince and Other Tales” collection. We talk about it with Antonio Tancredi, director of Cattivi Maestri company.

“The selfish giant” by Oscar Wilde is a fairy tale full of symbols. What does it tell about?

The protagonist himself, the giant, refers to something else as well as the garden, seasons, spring that remains outside the garden while the frost and the snow are the masters, the child who asks the Giant to help him climb on the tree. As in the ancient fairy tales, Wilde tells a story which refers to something else and which has a precise function: even before being pedagogical, the Selfish Giant’s tale is a recovery tale, which heals the listener, it gives relief. And what is relief if not a change of condition that helps us, as in the tale, to reach a different level, lifting us to the top of the tree. The selfish giant refers to those who are too high to see who is below, whether they are children, as well as those who are socially and economically worse off. It’s not difficult to match the character of the story to those many who build walls to prevent others from entering their rich garden to be able to live there with their families. I don’t know if Oscar Wilde thought of these possible interpretations of his tale, but his story, regardless of him, talks even about this. Writers know that stories can have a life of their own, going beyond the initial mentions of the authors themselves.

The tale in question is quite easy and linear: a giant, after seven years being guests of its cousin, comes back home. In those seven years, its beautiful garden had become a playground for children from a near town. The giant could embrace this new circumstance or decide to send away children; and this is what he did. But it brings consequences. Choosing to build a wall that protects his garden, the giant condemns itself to isolation and loneliness. And what is loneliness if not a lack of contact, relationship, exchange? What is loneliness if not the other side of the coin of selfishness, which is another form of loneliness? Selfishness, this kind of selfishness, in fact requires that all space be occupied by one’s ego. For this reason, in the tale, there can be no space for others, nor for children. But loneliness sometimes becomes intolerable even for those who seek it as a barrier to the outside world; however, it was not the effect our giant wanted: in the story, frost and snow replaced the spring and the loneliness experience will create premises to the children’s return and the encounter between the giant and a very small child who wished to climb on trees without succeeding. It’s him, who thanking the giant with a kiss, will conquer its heart, who at this point will demolish the walls. In the original story the child is Jesus, in ours instead he represents the childhood. And what is childhood if not humanity’s spring? If childhood is missing, what are we left with but a freezing winter? It is through the relationship with childhood that the adult rediscovers also his garden and realizes that this can acquire a different meaning. His sharing will make that garden bloom again.

The message of the story is the importance of socializing and sharing. What is the difference among the initial friendship between the Giant and the Ogre, and the rediscovery toward children? When does the Giant’s metamorphosis occur?

In the original story, the friendship between the Giant and the Ogre is briefly described and it was needed to create the giant’s absence from his garden and the birth of nostalgia. In shaping the show, we wanted to expand it to tell how the giant relates to others of the same shape: with the Ogre, the Giant talks about the common past, but competitiveness always emerges in this past, the attempt to assert one’s own superiority over the other. Both often repeat “I”. It’s true, even in childhood – and not only – there are moments in which the affirmation of one’s self with respect to the outside is essential, but this is soon overcome by a mediation that favours relationships. In the relationship with the Ogre, however, something childish persists, in the good sense of the term. The childhood’s memory, despite of creating a competitive game, it helps to not turn off the giant’s childhood, mean as spiritual quality. A child will reawaken it. This occurs with a kiss, as in the classical tale “Sleeping Beauty”. Wilde entrusts to the kiss, another symbolic element, the power of awakening. This happens when the giant and the child are on the same level. This element also reminds us of how important is for a relationship to be created and in this case a relationship that is love, on an equal level.

Two nomads are going to tell the audience the story of the selfish giant. Who are they?

When we stage a traditional fairy tale, we wonder who are those who act, and, if they tell, why they do that, which is their function. In this case we thought of two nomads Route and Road – both names recall the road, in French and English. And what are actors if not nomads who are constantly traveling between squares and theatres? We imagined that Route and Road in their wandering, not only collect tales, they even tell them. To do that they ask permission and try to win the audience’s scepticism. And through the tale, the wall, the one of the story and the one between the audience and narrators, will be demolished. In fact, demolishing walls is even a purpose of the theatre.

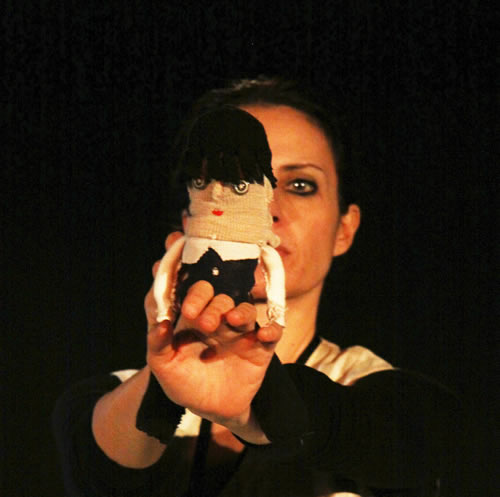

The story is told with the use of objects. What objects are we talking about?

First a carpet, a little carpet which becomes for us the tales’ carpet. Of all possible and impossible stories. We stole the idea from Peter Brook – “stole” is a strong term, probably it would be better saying we borrowed it, like Brook did with the Eastern culture. The carpet is the place where we stop, meet, barter, sell, buy, rest and fall asleep: it is home and story. The carpet, with its limitations, can collect infinite imagery. At the beginning the set will be bare, everything will be built on, inside and outside the carpet that the two actresses bring with them on stage. But, if the carpet is both home and stage, suitcases contain stories: everything needed to tell will come out of them. Everything has its own meaning and leaves a mark. Children and the audience’s imagination will add the remainder, so a suitcase with a window will become the giant’s house; flowers will mark the garden and an umbrella the foliage of the tree. Maybe a “poor” theatre, done with little, but just enough. And certainly not of ideas. A theatre thought for travelling and going everywhere.

The play tells the beauty of warmth moments; are cold moments even necessary? Which is their role?

In the play there is a moment in which the snow asks the Giant: “What do you do with a pale sun that is sometimes there and sometimes not! Don’t think about doing without us. We are here and here we’re staying!”. In our lives we faced tough, hard and critical moments. However, it is a natural, physical law that spring arrives after winter; we don’t hope for spring to come, we know it will come. And it is precisely the frost that allows us to recognize the spring, its warmth and its colours. Sometimes it is inevitable to go through frost moments. As long as these aren’t that long. And, certainly, the support and relationship with the others, the sharing helps us to overcome them sooner.

“Il gigante egoista” will be staged on the 12 August at the Boschetto Parco Ciani at 20:30, during the Summer Family season.

Learn more: luganoeventi.ch